3:30 PM

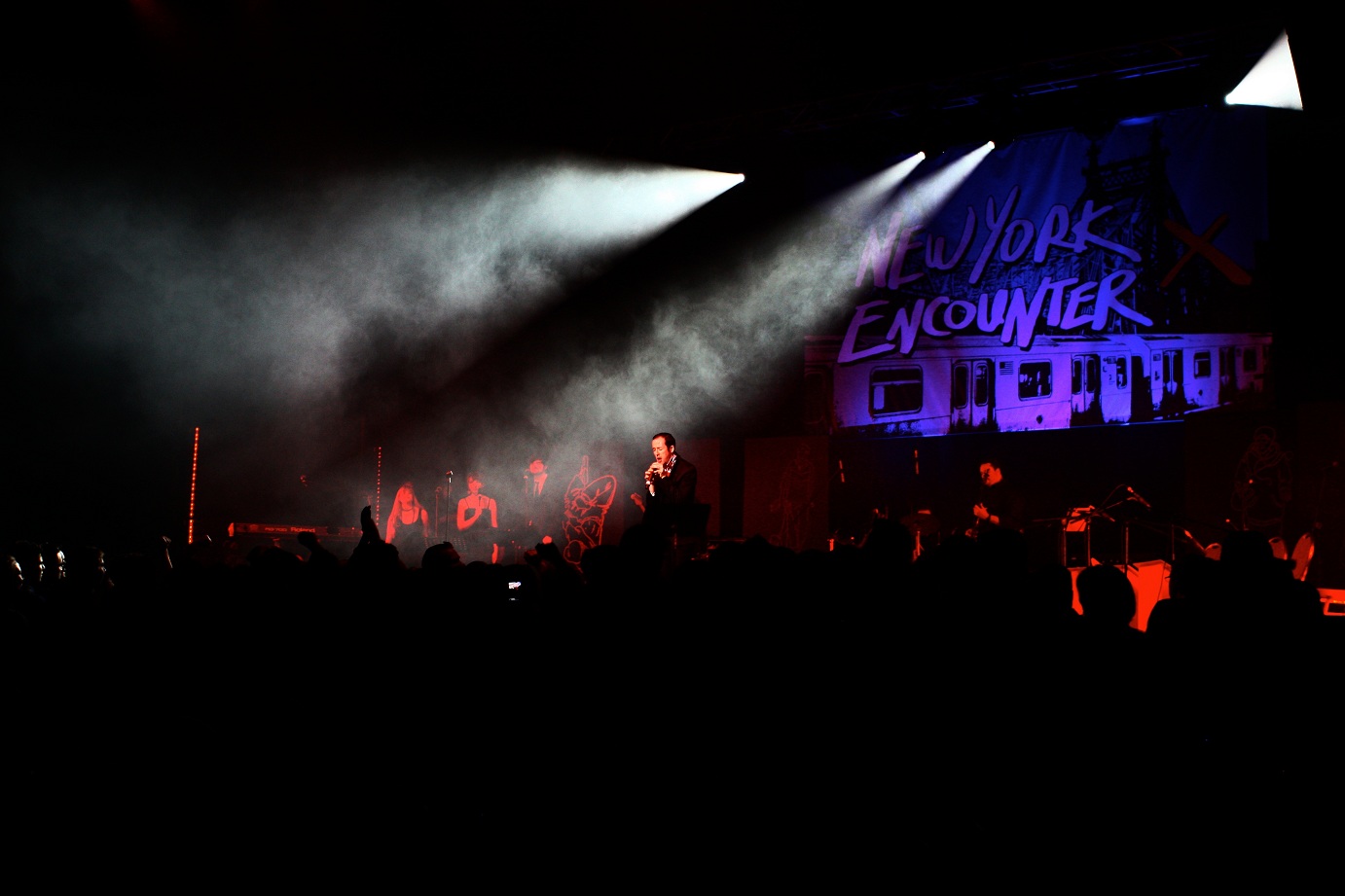

3:30 PM Ferenc Fricsay: The Greatness of the Person

A screening of conductor Ferenc Fricsay’s last rehearsal of Smetana’s “The Moldau”, recorded shortly before his death, presented by Jonathan FIELDS, musician.

A screening of conductor Ferenc Fricsay’s last rehearsal of Smetana’s “The Moldau”, recorded shortly before his death, presented by Jonathan FIELDS, musician.

(Ferenc Fricsay, during his last rehearsal of Smetana’s “The Moldau”)“You must enjoy the sound, along with me. More movement! […] How beautiful is to live! Here it is! It is really beautiful to live! Living is the most beautiful thing!”

(Sir Yehudi Menuhin, violinist)“It is ideal when a soloist and a conductor can arrange for a series of concerts, for instance if they can go on tour together and have time to reach the essential musical truth that each one is striving for. I had this good fortune with Ferenc Fricsay. The tour we did together through Germany to Copenhagen, London and Paris will always remain in my memory as a musical and human experience that was both inspiring and touching. I was not only able to enjoy the complete agreement in our understanding of the works played in my part of the program, but better I had the opportunity to watch and analyze the extraordinary way in which he dramatized each musical score. Each work became a novel fraught with human passion, with moments of crises and thanksgiving, of joy and agony, all strung together in a continuous story, which his imagination wove in greatest detail. He created such drama in his music-making that it seemed to me he would need no other literature in his life.”

(Maria Stader, Swiss soprano)“What amazed me most was Ferenc Fricsay’s intuitive relationship to the vocal. It isn’t presumptuous in this case, to talk about a sixth sense, so perfect was his empathy for the human voice. He went as far as to give us valuable advice, although he had never had any training as a singer nor had he ever studied the complicated physiological process of singing. His advice helped me personally on my way and it helped other singers as well.

For him, music was absolutely fundamental. That was why the mere word “routine” was hateful to him, to say nothing of a routine singer or a lethargic routine orchestra. Situations like these made him totally helpless; he felt personally insulted and his beloved music violated. In such occasional moments of clashes with his colleagues he forgot diplomacy and flew into a rage. “You don’t care at all about music," he once snapped at a colleague, “You only sing notes!” In these matters he would not accept a compromise. In rehearsals that didn’t turn out to his satisfaction or when he felt opposition, he was driven to desperation. He needed mutual response, attention, an echo for his intentions. Once this echo was created, he was able to lead his colleagues to the highest levels of accomplishments.”