10:30 AM

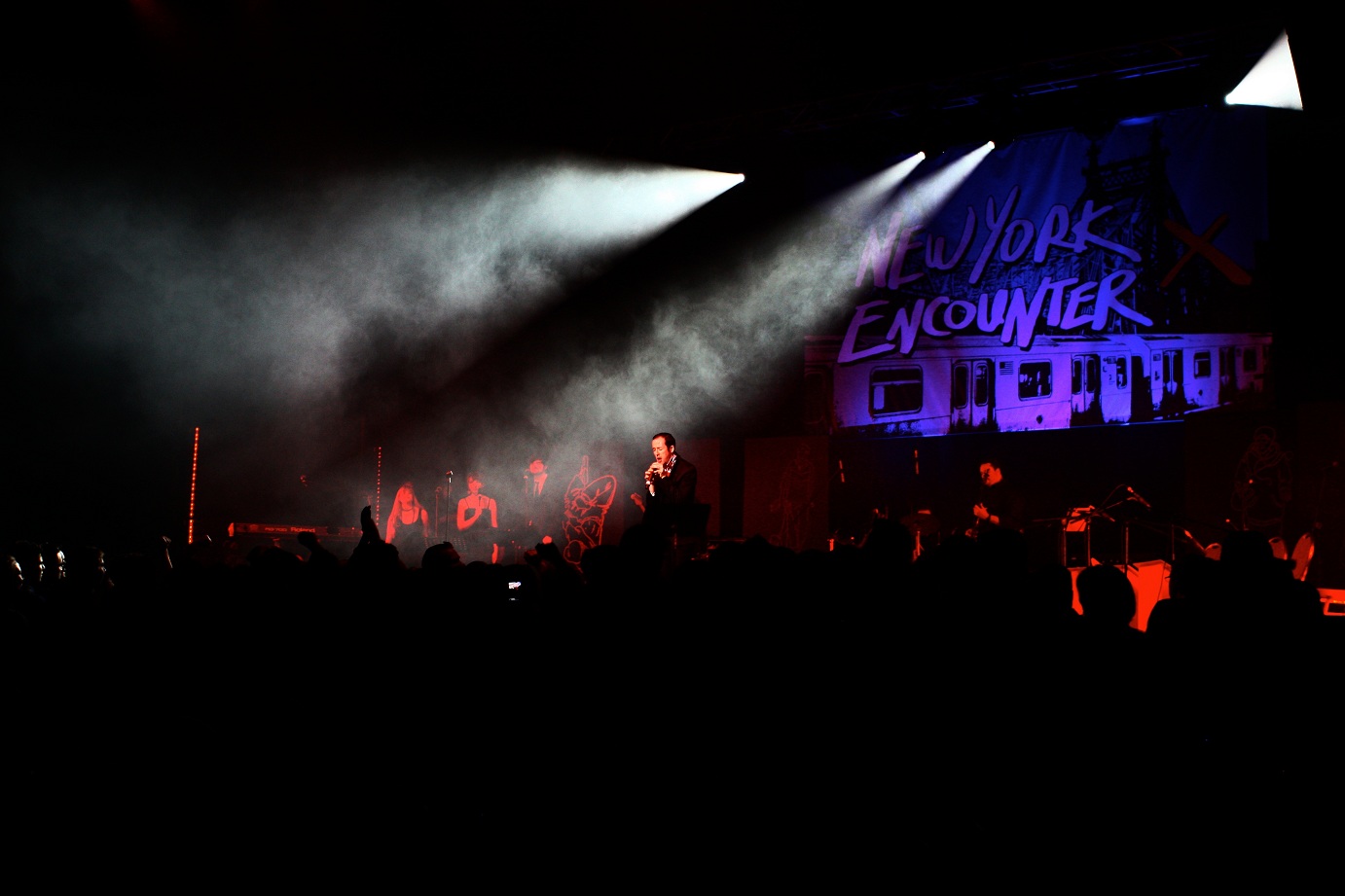

10:30 AM  New Yorker Hotel

New Yorker Hotel Giacomo Leopardi: Infinite Desire

A homage to the Italian poet on the occasion of the publication of his poems in the U.S. with Jonathan GALASSI, President and Publisher of Farrar, Straus and Giroux; Davide RONDONI, Author and Poet; and Joseph WEILER, University Professor at NYU School of Law

Jonathan Galassi, President and Publisher of Farrar, Straus and Giroux, has published two books of poems: “Morning Run” (1988) and “North Street” (2000). He has produced widely acclaimed translations of several volumes of the work of the Italian poet Eugenio Montale. Recently Galassi completed a strong, fresh, direct version of Leopardi’s work that offers English-language readers a new approach to this great modern poet. To learn more about Canti: Poems / A Bilingual Edition, released in October, 2010 by Farrar, Straus and Giroux, click here.

Read the New York Times review of Canti here.

Transcript of the Discussion:NEW YORK ENCOUNTER 2011 - Infinite Desire

An homage to Giacomo Leopardi on the occasion of the

publication of his poems in the U.S.

Speakers:

Jonathan GALASSI, President and Publisher of Farrar, Straus and Giroux,

Davide RONDONI, Author and poet,

and Dr. Joseph WEILER, Joseph Strauss Professor of Law, New York University

Moderator: Gregory WOLFE, Editor of Image

Presented by Crossroads Cultural Center and Communion and Liberation

Monday, January 17, 2011, The New Yorker Hotel, Grand Ballroom, NYC

Wolfe: Good morning and welcome to all of you on behalf of New York Encounter. This is the final session for New York Encounter 2011. We hope it’s a last but not least scenario.

I don’t know about you, but I’m having “Déjà vu.” It seems that on Monday of Martin Luther King Day, I am chairing a literary panel featuring a distinguished editor from Farrar, Straus and Giroux. That’s referring to last year’s session. We had a wonderful session at just exactly the same time with Paul Elie, and it’s great to be here and to represent literature at the festival.

My name is Gregory Wolfe. I’m the editor of Image journal and I direct the low-residency MFA in Creative Writing at Seattle Pacific University. I am an expert on Leopardi’s poetry. My expertise, as the expertise of so many people these days, derives from my having read the Wikipedia entry on Leopardi, that is sufficient, I would say, at least in the modern technological era. Actually, like many of you in the audience, I only know Leopardi secondhand through my encounter with him in the writings of Luigi Giussani, the Italian Monsignor and founder of the movement Communion and Liberation, and you might say that’s an unfortunate distance from the original source, but I think sometimes one great mind, one great artist, one great thinker can help awaken us and awaken an entire culture in a period of time to another artist. Think of the way Charles Dickens brought a Shakespearean cast to life in his books, or the way that Mendelssohn rediscovered Bach or the way that T.S. Eliot rediscovered Dante for our time, certainly for English-speaking readers. In that sense, I really believe that Luigi Giussani in many ways captured some of the essence, the genius of Leopardi in the many short passages and allusions to him that we’ve encountered in reading his books.

I’ve like to remind everyone of the story that Fr. Giussani told of how Leopardi played a crucial role in his life. Giussani once wrote:

I was a young seminarian in Milan, a good, obedient, exemplary boy. [And he was a boy; you know how young they started back then.] But, if I remember correctly what Concetto Marchesi says in his study of Latin literature, “Art needs men who are moved, not men who are devout.” Art, that is, life – if it is to be creative, that is, if it is to be “alive”—needs men who are moved, not pious. And I had been a very devout seminarian, with the exception of an interval of a month during which the poet Leopardi gripped my attention more than Our Lord.2

Camus says in his Notebooks: “It is not by means of scruples that man will become great; greatness comes through the grace of God, like a beautiful day.” For me, everything happened like the surprise of a “beautiful day,” when one of my high school teachers—I was then 15 years old—read and explained to us the prologue of the Gospel of St John. At that time in the seminary, it was obligatory to read that prologue at the end of every Mass. I had therefore heard it thousands of times. But the “beautiful day” came: everything is grace.

As Adrienne von Speyr says, “Grace overwhelms us. That is its essence. It does not illuminate point by point, but irradiates like the sun....”

Forty years later, reading this passage from Von Speyr I understood what had happened to me then, when my teacher explained the first page of the Gospel of St John: “The Word of God, or rather that of which everything was made, was made flesh,” he said. “Therefore Beauty was made flesh, Goodness was made flesh, Justice was made flesh, Love, Life, Truth were made flesh. Being does not exist in a Platonic nowhere; it became flesh, it is one among us.” And then I recalled a poem by Leopardi, a poem I had studied during that month of “escape” in my third year of high school, entitled: “To His Lady.” It was a hymn not to one of Leopardi’s many “loves,” but to the discovery that he had unexpectedly made ... that what he had been seeking in the lady he loved was “something” beyond her, that was made visible in her, that communicated itself through her, but was beyond her. This beautiful hymn to Woman ends with this passionate invocation:

Whether you are the one and only

eternal idea that eternal wisdom

disdains to see arrayed in sensible form,

to know the pains of mortal life

in transitory dress;

or if in the supernal spheres another earth

from among a numbered worlds receives you,

and a mirror star lovelier than the Sun

warms you and you breathe benigner ether,

from here, where years of both ill-starred and brief,

accept this hymn from your unnoticed lover.

In that instant I thought how Leopardi’s words seemed, 1,800 years later, to be begging for something that had already happened and had been announced by St John the Baptist: “The Word was made flesh.” ...

That is the whole story. My life as a very young man was literally invaded by this; both as a memory that continually influenced my thought and as a stimulus to make me reevaluate the banality of everyday life. The present moment, from then on, was no longer banal for me. Everything that existed—and therefore everything that was beautiful, true, attractive, fascinating, 3 even as a possibility—found in that message its reason for being, as the certainty of a presence and a motivating hope which caused one to embrace everything.

And so hearing that story and encountering Giussani’s allusions to Leopardi is, I think, a great introduction. And now with Jonathan Galassi’s translation, we have an opportunity to delve deeper. So it is my great pleasure to introduce our first speaker.

Jonathan Galassi was born in Seattle, Washington, in 1949. He attended Phillips Exeter Academy, Harvard College, and Cambridge University, where he earned an M.A. in 1973. Mr. Galassi became an editor in the trade division of Houghton Mifflin Company in 1973. He was a senior editor at Random House from 1981 to 1986, when he joined Farrar, Straus and Giroux as vicepresident and executive editor. He was named president of the firm in 2002. Mr. Galassi has published two books of poems: Morning Run (1988) and North Street (2000) and has translated several volumes of the work of the Italian poet Eugenio Montale. He recently completed a translation of the poetry of Giacomo Leopardi, Canti: Poems / A Bilingual Edition, released in October, 2010.

He has published poems in literary journals and magazines including Threepenny Review, The New Yorker, The Nation and the Poetry Foundation website.Please join me in welcoming Jonathan Galassi.

Galassi: Thank you very much. It’s an honor to be here and to speak to a group who have a particular angle of approach to a poet like Leopardi. Leopardi grew up in a very conservative Catholic family and he rebelled against that very deeply. His mother was a very, very religious and repressive woman, I’d say, and his father was more feckless and had a huge library of Patristic literature, but also classical literature. When Leopardi discovered Greek literature, he fell in love and I think he saw that as a way out of what he saw as a constricting atmosphere of his family. He adopted stoicism, Epicureanism as his mental set, but I think that you can see in Leopardi a kind of war between the ideas that he decided were going to be his ideas and, as Gregory was implying in quoting Fr. Giussani, there’s a kind of desire for something beyond the world of the present which he posited as the only thing there was, but there’s always a kind of regret, a kind of lack, a kind of sense of something missing that informs his work, and I think that you can interpret that as a kind of obverse of Christianity in a way.

I found this also in Montale, a poet I worked with before, who called himself an agnostic, but there’s always a sense of something missing in his sense of the world. There is a lot of talk about God, but it’s a God who can’t be fully admitted. Leopardi doesn’t talk about the Christian God, but he does talk about desire and I think that’s the theme of today—that sense of desire for union with the world that can be interpreted in a religious way. I thought I’d read a few poems, short things, that reveal some of these paradoxes in Leopardi. A poet as great as Leopardi can probably be seen in whatever way you want to see him; there’s so much in him that we can find things to attach to that resonate with our own desires. That doesn’t mean that it’s not there, but I think that it’s a 4 very complicated, endless regression of approaches to reality that someone as deep as this…I’m going to read L'infinito, his most famous poem which he wrote when he was very young, and you’ll see why. I call it Infinity:

This lonely hill was always dear to me,

and this hedgerow, which cuts off the view

of so much of the last horizon.

But sitting here and gazing, I can see

beyond, in my mind's eye, unending spaces,

and superhuman silences, and depthless calm,

till what I feel

is almost fear. And when I hear

the wind stir in these branches, I begin

comparing that endless stillness with this noise:

and the eternal comes to mind,

and the dead seasons, and the present

living one, and how it sounds.

So my mind sinks in this immensity:

and foundering is sweet in such a sea.

The dialogue, the contrast between the present and the infinite is the space in which Leopardi’s thought and poetry takes place. I’m also going to read a poem from later Leopard; it’s called On the Portrait of a Beautiful Woman. It’s inspired by a funerary sculpture. There’s a lot of involvement with death in Leopardi’s poetry and with the fact that there’s nothing but death. But if you say there’s nothing but death, that makes you think that maybe that’s not true.

On the Portrait of a Beautiful Woman Carved on Her Burial Monument You were this: but here, now, underground

you’re dust and skeleton. Raised and set

above your mud and bones to no avail,

the image of your former beauty stands

in silent witness while time flies,

sole guardian of memory and grief.

The gentle look that made men tremble

when you turned to them, as you do now,

the kip from which deep pleasure seemed to overflow

as from a brimming urn, the neck

once circled by desire, the loving hand,

which when it was given often felt

the hand it took go cold;

and the breast,

which meant that men

went visibly pale—

all of these were once upon a time.

Now you are mud and bones. A stone

hides the indecent, miserable sight.

So destiny reduces5

the look that seemed the brightest

image of heaven among us. Eternal

mystery of our being. Ineffable

source of noble and immense ideas

and feelings, beauty reigns today

and seems, like splendor

lavished on these sands by a divine being,

a sign of reassuring hope

for superhuman destinies,

for blessed realms

and golden worlds for mortals.

Tomorrow, without warning,

what was almost angelic to behold

becomes repulsive to the sight,

detestable, unworthy,

while the admirable idea

that emanated from it

Music’s learned harmony

naturally engenders

infinite aspirations and exalted

visions in the dreaming mind;

thanks to which the human spirit

moves in a delicious, unknown sea,

almost the way a daring swimmer

dives into the ocean, for enjoyment.

But if a discordant

note assails the ear,

that heaven turns to nothing in an instant.

Human nature,

if you’re merely weak and worthless,

dust and shadow, why aspire so high?

But is you’re partly noble,

why are your best actions and intentions

so easily, by such unworthy causes,

both inspired and undone?

It’s very abstract poetry, but it goes the heart of what we’re talking about today. I think Leopardi is a very hard poet to translate because he really deals in ideas, and what dresses up those ideas and makes them poetry is the sound of his words. He uses imagery very sparingly, but the sound of his poetry is magic, and I can’t do that with English. I can try but it’s very hard to come anywhere near the beauty, the natural purity and rightness of every line that makes him…that’s why he’s studied in school. So you have to add that in when you’re reading a translation. You have to imagine that.6

Anyway, that’s a little bit about Leopardi in the context of your meeting today. Thank you.

Wolfe: Thank you so much, Jonathan. Our next speaker is Joseph Weiler who is the European Union Jean Monnet Chair at NYU Law School. He serves as Director of The Straus Institute for the Advanced Study of Law & Justice and The Tikvah Center for Law & Jewish Civilization. He was previously Professor of Law at Michigan Law School and then Manley Hudson Professor of Law and Jean Monnet Chair at Harvard Law School. His publications include Un’Europa Cristiana (translated into nine languages), The Constitution of Europe – “Do the New Clothes Have an Emperor?” (translated into seven languages), and a novella, Der Fall Steinmann.

Please welcome Joseph Weiler.

Weiler: Thank you very much. For me too it’s an honor and a privilege to be here, and even more mysterious why I was asked to be here. I think he [Davide Rondoni] is the culprit.

Giussani of course was a great theologian and thinker, but in my mind, above all, he was a remarkable educator. He understood profoundly that there’s a difference between reading a wonderful essay about love, and the experience of loving somebody. Or between reading an essay about friendship and then the experience of having a friend. These are two different types of knowledge. One is cognitive and one is experiential. You get to know friendship in two different ways. In Christianity, unlike Judaism, beauty is essential, central, indispensible. It has an importance which goes beyond esthetics and civility. But Giussani understood that it wasn’t enough to explain cognitively, philosophically, theologically the importance of beauty, but that one had to make that move from an essay about friendship to having a friend, and that’s why, for example, with the power of his personality and his charisma, he had people listen to beautiful classical music through the community that he established because he knew that no amount of talking about the beauty of music would be able to capture the experience of actually listening to it and experiencing it. I am sure, (and this is not to diminish or demean anybody), that if it were not for Giussani thousands and thousands of people among his followers would never experience the beauty of Schubert’s Trios Opus 99 and Opus 100 or many of his other favorites.

The same goes for poetry.

What we do in our culture is to turn people away from poetry. It’s a very important part of our culture; some people understand that, so it becomes part of the curriculum in high school. Leopardi should not be taught in high school. It is not for young children. It is not for adolescents either. For most students, the last time they will have looked at Leopardi is at the time they prepared the final exams at school and then, with a blessing to the Almighty, put him away for ever. Once again it’s the deep insight, his great gift to understanding the challenge of education that Giusanni understood— that instead of talking about Leopardi, he had to have young adults reacquaint themselves with him, actually read Leopardi.

Thus Giusanni talks about the importance of Leopardi from a cognitive point of view and a theological point of view. We don’t want to live a life of self-satisfaction. There’s always something missing in our life. It’s almost normative that there should be something missing; there should always be a yearning. But apart from the point 7 that he makes, he makes people actually go and read Leopardi and experience that absence, that yearning, not through the wise words of an essay but through the esthetic experience of reading a poem.

If you are serious about poetry, it has to be disciplined – the way prayer has to be disciplined. Sure, before your plane crashes you may want to say a quick prayer, it may help or may not help but it will certainly not capture the experience of prayer in life. (I must tell you this Jewish joke. Maybe I’ve told it already. There’s this guy who’s fallen off a boat and he’s drowning. So they throw him a life jacket and he said, “No, I trust in God; God will save me.” So they say, “Don’t be a fool!,” and they throw him a rope, and he said, “I trust in God; God will save me.” So they see that they’re really dealing with a fool, and they put a boat in the water, and they go to rescue him and he says, “No, God will save me.” And he drowns. So the angels go to God and they say, “How could you have let a man with such great faith drown?” And God says, “What can I do? I sent him a life jacket, I sent him a rope, I sent him a boat?”) Prayer is not 911!

The discipline of prayer comes not from the moment when you are exalted or in great fear, but from the daily discipline, the repeated experience, and if you’re disciplined in prayer, you have to be equally disciplined in poetry. You cannot capture it if you do not read it repeatedly, again and again, and make it an integral part of your life.

I do not plan to make Leopardi an integral part of my life. Sorry Don Giusanni! I have very ambivalent feelings about Leopardi, and I will share them briefly with you. On the one hand I admire his profundity and I admire most his incomparable lyrical expressionism, deeply romantic. The way I want to illustrate it is through the poem Hymn to the Patriarchs, or on the Origins of the Human Race. It is most apparent when you compare his rendition to the Biblical original.

Genesis 1:11-13: Let the earth grow grass, plants yielding seed of each kind and trees bearing fruit of each kind, that has its seed within it upon the earth.” And so it was. And the earth put forth grass, plants yielding seed of each kind, and trees bearing fruit that has its seed within it of each kind, and God saw that it was good. And it was evening and it was morning, third day. (Alter)

This incidentally is a new translation by Robert Alter. We are all used to King James, but I think Robert Alter had a very nice quip about King James. He said, “It’s wonderful on the English, but it’s really weak on the Hebrew.” So he re-translated the Bible. It’s worth reading…The Pentateuch. So you’re familiar with that. It’s Genesis 1; it’s majestic; it’s universal; it’s awesome; it’s awe inspiring. I have to read one other thing: The next day:

Genesis 1: 14-18: And God said, “Let there be lights in the vault of the heavens to divide the day from the night, and they shall be signs for the fixed times and for days and years, and they shall be lights in the vault of the heavens to light up the earth.” And so it was. And God made the two great lights, the great light for dominion of day and the small light for dominion of night, and the stars. And God placed them in the vault of the heavens to light up the earth and to have dominion over day and night and to divide the light from the darkness. And God saw that it was good. And it was evening and it was morning, fourth day. (Alter)8

Leopardi is saying the same thing, in talking about Adam:

You, ancient guide and father

of the human family, were the first to see the day,

the purple fires of the revolving stars,

the newborn flowering fields,

the wind that blows across the freshened meadows,

when the cascading alpine waters

struck the cliffs and uninhabited

valleys with the unheard sound; when unheard-of peace

reigned in the pleasing future habitats

of happy peoples in their busy cities…

See the difference? I read this deliberately because normally we would not dare to compare something to the Bible. We would say, let the Bible stand in its majesty.

But through the poetry… “day and night…it was the fourth day”… “and He created the big light for the dominion of the day.”

I’m going to read Leopardi again:

You, ancient guide and father

of the human family, were the first to see the day,

the purple fires of the revolving stars,

the newborn flowering fields,

the wind that blows across the freshened meadows,

when the cascading alpine waters

struck the cliffs and uninhabited

valleys with the unheard sound; when unheard-of peace

reigned in the pleasing future habitats

of happy peoples in their busy cities…

It’s a totally different experience. It’s the difference between reading about the creation of the world and experience what it must have been to humanity for the first time to become conscious of experiencing the world. There are things that poetry can do which no other genre of human communication can do, and Leopardi does it as well as anybody else.

Let’s go to Abraham. Chapter 18 of Genesis, a wonderful chapter!

Genesis 18: 1-5: And the Lord appeared to him in the terebinths of Mamre when he [this is Abraham] was sitting by the tent flap in the heat of the day, and he raised his eyes and saw. And look, three men were standing before him. He saw and he ran towards them from the tent flap and bowed to the ground and said, “My Lord, if I’ve found favor in your eyes please do not go past your servant. Let a little water be fetched and bathe your feet and stretch out under the tree. And let me fetch a morsel of bread, and refresh yourself. Then you may go on for you have not come by your servant. And they said, “Do as you have spoken.” (Alter)9

It’s the famous story of when Abraham meets the three messengers. Famous…How many of you have read it? We all know: Catholics do not read the Bible…Now this is Leopardi on Abraham, the very same scene:

My heart is meditating on you now,

father of the faithful, just and strong,

and on your brave descendants. I shall tell

how, as you sat alone at sunset in the shade

of your peaceful house, along the gentle banks

that fed and rested your flock,

heaven’s holy pilgrims dressed as men

blessed you;

It’s describing the same scene, but it’s the difference between an essay on love, a piece of history, and the experience of loving; an essay about friendship and actually having a friend. That’s what poetry does and that’s what Leopardi, at a young age, audaciously (if you want to be vulgar) takes on the Bible and brings it to us. Why don’t I like Leopardi? I will tell you too. Because he’s too romantic. The future is always promising; the past is always idealized, but the present is comprehensively deceptive, disappointing, sad, melancholic. I often wonder why Giussani loved Leopardi so much. I understand Giussani’s great imperative to have us live a life where there’s always something missing, where there’s always yearning. That yearning is indispensible for the homo religiosus. Leopardi correctly sees our present, fallen, imperfect human condition. But in his poems I find no pardon, no forgiveness, no pity for existing humanity. And to me that is so un-Jewish, unChristian, un-Giussani. That is why I keep a distance from Leopardi. In my understanding or my reading of him he is a man with love of beauty and nature but no love for himself, no love for his fellow human beings. In a triple sense Leopardi violates the greatest imperative of the entire Bible: VeAhavta LeReacha Kamocha, Ani Hashem. Thou shalt love thy neighbour as thyself: I am the LORD! (Leviticus 19:18) Leopardi has no love of himself, no love of his fellow human beings and no love of the Lord. I have little patience for such. Thank you very much.

Galassi: I found that a very fascinating talk. I’d like to say two things. One is, I think that where that forgiveness or where the chink in Leopardi’s armor is is in his description of illusions. Love he thinks is an illusion. Joy is an illusion. But as he says many times, those are the only things that make life worth living—the illusions. So he actually subscribes to something he doesn’t believe in, and I think that that’s the paradox of Leopardi.

The other thing I’d like to say is that Robert Alter is a wonderful scholar, etc…, but as far as English goes, I’ll take King James any day.

Weiler: Me too.

Wolfe: And now I’ll introduce our final speaker, my friend, Davide Rondoni. one of the most interesting voices in new Italian poetry, was born in Forlì in 1964. He received his degree in Italian literature from the University of Bologna, where he is the director of the Centre for Contemporary Poetry as well as editor of the literature magazine Il ClanDestino (The ClanDestine).10

Rondoni has published several books including Il bar del tempo (The Bar of Time, 1999), which won several literary prizes, and Non sei morto, amore (You Are Not Dead, Love, 2001). His most recent collection of poetry is Avrebbe amato chiunque (He Would Have Loved Anyone, 2003). Together with Franco Loi, he edited the anthology Il pensiero dominante: Antologia della Poesia italiana 1970-2000 (The Dominant Thought, Anthology of Italian Poetry 1970-2000).

His work has appeared in various anthologies and magazines in Italy and abroad. In addition, he writes fiction and theatrical pieces and has translated Rimbaud, Baudelaire, Péguy, T.S. Eliot and Dickinson. He has also edited an anthology of Giacomo Leopardi’s writings, as well as a poetic version of the Psalms. Rondoni organizes various literary events and television programs. His poems have been translated in Russia, the United States, England, and Spain.

And to translate for him, we are very pleased to welcome Gregory Pell. Prof. Pell is Associate Professor at the Department of Romance Languages and Literature at Hofstra University and has translated many of Davide Rondoni’s poems into English.

Please welcome Davide Rondoni.

Rondoni: Good morning. I want to speak Italian for four reasons. The first is, my English is not so great; second because the Consul General of Italy is here; three because, quite frankly, after hearing a number of foreigners speaking English lately, it would have been better if they had spoken in their native tongue; and fourth, if you’re going to talk about Leopardi, let’s do it in the original language.

Leopardi is an immense man and thinker. He inspired people like Nietzsche. His philosophical thought is at the level of someone like a Hertlein or a Butler. With him we can go on so many different journeys. My journey begins with an expression Leopardi pronounced more or less on his deathbed, something that moved me greatly, something that he said to his friend right before passing, and that is, “I will no longer see you.” It’s something I would never want to have to say. I would always want to see the beloved faces of those I love. In talking about On the Portrait of a Beautiful Woman Carved on Her Burial Monument, the primary theme in Leopardi is the beauty of that which can be seen, and that those things that will disappear and go away. He focuses on a great contradiction—that of seeing something beautiful but at the same time seeing almost nothing. The beauty of a woman or of nature brings up the irresolvable problem of this issue.

Before going forward I want to set a preamble here and discuss why we even talk about poetry. Why do we even read poetry? Sure it’s part of our culture, but more importantly it’s an anthropological phenomenon. Everyone has had an experience of poetry. For example, when we fall in love, we don’t say, “Laura Rossi, I love you.” The name that appears on the birth certificate is no longer important, for women, for children, for anyone. We need to invent names. You call her, “my little flower,” “my little pony,” “my little rabbit.” When reality strikes us, when it moves us, and reality can be a woman, it can be Jesus Christ, normal language, regular language is no longer valid; it’s not useful to us. When reality truly strikes us, when it has an impact on us, we have to invent words so that we can ignite or set fire to this experience. And for that reason, Don Giussani’s language was poetic, and not because he was just a poet. He allowed himself to be moved by that which he was saying. And that’s how poetry arises among us as humankind. There are many poets even here present in this 11 room, Paolo Valesio, Jonathan Galassi…This habit, this experience of giving nicknames to the world is a very human experience, a very particularly human way of doing things. Leopardi, in fact, has given names of various times and they’re still relevant, still valid for this experience.

What does it mean to really understand a poem? I have conferences all the time and people say, “Ah, who gets poetry? I don’t get it.” And I respond, “Do you understand your wife?” What does understanding really mean? Poetry accompanies you in time. You get it. You take it with you. You don’t understand it as if it were a dialogue. As Don Giussani said, “My whole life I kept reading, experiencing and repeating Leopardi.” In my personal journey through Leopardi, one thing is truly important, one major point is necessary to understand—life is a contradiction. Man is just a naturally contradictory being. He cannot be solved or remedied by himself. A very important expression that Leopardi pronounced in 1923 and I’d never heard before what year this was, he said, “Nothing in the world, when speaking of the greatness of human intellect, the ability of humankind, nothing can strike you so much as how small we really are in this world of ours, this globe.” And when man finds himself in the middle of this vastness, this immensity, he says, and Leopardi says, “I almost, almost confuse myself with nothing. I’m almost nothing.” Man is almost nothing. It’s a very odd word, almost. Quasi nulla, it’s almost nothing is a contradiction. Either it’s nothing or it’s almost. Try telling a woman she’s almost beautiful! This is the great litmus test or line of departure, barrier. He always comes back to this issue of almost nothing. It’s like Night Song of a Wandering Shepherd in Asia and this is Jonathan Galassi’s translation: And I say this on behalf of my friend, Joseph Weiler, this has to be read as a Psalm. It’s a Psalm of modernity.

What are you doing, moon, up in the sky;

what are you doing, tell me, silent moon?

You rise at night and go,

observing the deserts. Then you set.

Aren't you ever tired

of plying the eternal byways?

Don't you get bored? Do you still want

to look down on these valleys?

The shepherd's life

is like your life.

He rises at first light,

moves his flock across the fields, and sees

sheep, springs, and grass,

then, weary, rests at evening,

and hopes for nothing more.

Tell me, moon, what good

is the shepherd's life to him

or yours to you? Tell me: where is it heading,

my brief wandering,

your immortal journey?

Little old white-haired man,

weak, half-naked, barefoot,

with an enormous burden on his back,12

up mountain and down valley,

over sharp rocks, across deep sands and bracken,

through wind and storm,

when it's hot and later when it freezes,

runs on, running till he's out of breath,

fords rivers, wades through swamps,

falls and rises and rushes on

faster and faster, no rest or relief,

battered, bloodied; till at last he comes

to where his way

and all his effort led him:

terrible, immense abyss

into which he falls, forgetting everything.

This, O virgin moon,

is human life.

Can you hear this question? “What are you doing, moon, up there in the sky?” It’s an urgent question. It’s not one question; it’s actually two. At the end of this stanza which we’ve just heard, there is a terrible, terrible image: “a little old white-haired man” which Leopardi takes directly from Petrarch. Then the major is through sands, up mountains, through hole, through heap—ups and downs the way many of us experience them in life. Leopardi asks, What could all this serve? Where is this all leading? “Terrible, immense abyss/into which he falls, forgetting everything.” Nothing, and yet somehow more than nothing? But more than nothing is oblio, which, by the way, is a word we could say for forgetting in English, but also it’s much closer to the sense of oblivion in English. Oblivion is as if you had nothingness squared or doubled.

Okay, so, Leopardi, we’ve gotten that. Life is a sentence; it is nothingness. And that’s where he would end normally, but he doesn’t end the poem here. He keeps going. He’s one of those people who says, “Good-bye” to you and he’s still there talking. And he begins retelling his story. The poem goes on and he says:

Yet you, eternal solitary wanderer,

you who are so pensive, it may be

you understand this life on earth,

what our suffering and sighing is,

what this death is, this final

paling of the face,

and leaving earth behind, abandoning

all familiar, loving company.

And certainly you comprehend

the why of things, and see the usefulness

of morning, evening,

and the silent, endless pace of time.

Certainly you know for whose sweet love

spring smiles,

who enjoys the heat,

and what winter and its ice are for.

You know and understand a thousand things

that are hidden to a simple shepherd.13

Often, when I watch you

standing so still above the empty plain

whose last horizon closes with the sky,

or follow, step by step,

as I wander with my flock,

and when I see the stars burn up in heaven,

I ask myself:

Why all these lights?

What does the endless air do, and that deep

eternal blue? What does this enormous

solitude portend? And what am I?

This I ask myself: about this boundless,

splendid space

and its numberless inhabitants,

and all these works and all this movement

of all heavenly and earthly things,

revolving without rest,

only to return to where they started.

Any purpose, any usefulness

I cannot see. But surely you,

immortal maiden, understand it all.

This is what I know and feel:

that from the eternal motions,

from my fragile being,

others may derive

some good or gladness; life for me is wrong

You see these important, urgent questions: You, moon, know things I don’t. In reality this was based on a real Afghani shepherd. It was inspired by something around the equivalent of reportage of the day, the event. Every time you hear somebody talk about Afghanistan, he immediately thinks about this poem, this shepherd. I would give my leg to have written a couple of lines like this: “Certainly you know for whose sweet love/spring smiles.” Is the springtime sort of a moron’s smile or is he smiling at someone? Is life a fool’s smile or is it laughing or smiling at someone? He ends the poem with another sort of pronouncement or sentence:

Maybe if I had wings

to fly above the clouds

and count the stars out, one by one,

or, like thunder, graze from peak to peak,

I'd be happier, my gentle flock,

happier, bright moon.

Or maybe my mind's straying from the truth

imagining the fate of others.

Maybe in whatever form or state,

whether in stall or cradle,

the day we're born is cause for mourning.

Professor Weiler is correct when he says that Leopardi does not address or appreciate the present. There is no present for Leopardi because the present is devoured by nothingness. And the Christianity that Leopardi came 14 to know through his family was a Christianity without any charity or tenderness. It was bourgeoisie not Christianity. Very different things. He can’t love the present, and therefore he is a pessimist. For him, life is evil or bad. And you see it in Jonathan Galassi’s translation; he makes these pronouncements, these negative, pessimistic pronouncements about life being a bad thing or wrong, but he always precedes them with a “maybe” or a “perhaps.” If a person that you meet keeps saying, “Perhaps life is all wrong for us,” repeats it three times, it’s no longer a pronouncement. It becomes a question. To read Leopardi is to understand the provocation, the stimulus, the process of being moved by this question.

Wolfe: Well unfortunately we’re out of time. I know we could go much longer on the panel and kick things back and forth. This has really stirred us up in wonderful ways. I want to thank all of our panelists for their amazing contributions. It’s a pretty amazing thing for a young seminarian, Giussani, to decide that what was important was not to be pious, but to be moved. And whether we’re religious or not, I think this distinction is an important one. To be pious or to be abstract or ideological is to be removed from reality, to let our mind and our heart be separate. Poetry enables us to reconnect mind and heart, to be moved, and so it’s an important part of our life and so we’re always glad when translation can bring the language of another culture, another time to us. The most famous statement about translation is, in fact, an Italian statement, “To translate is to commit treason.” And we expect failure, but so often the beauty is that something does come through. I think that something tremendous comes through Jonathan Galassi’s translations and our panelists responded beautifully to it and I want to thank them once again.